“‘Successful’ art means something to my whole body…

[it] involves having an experience.”

— Metta Sáma

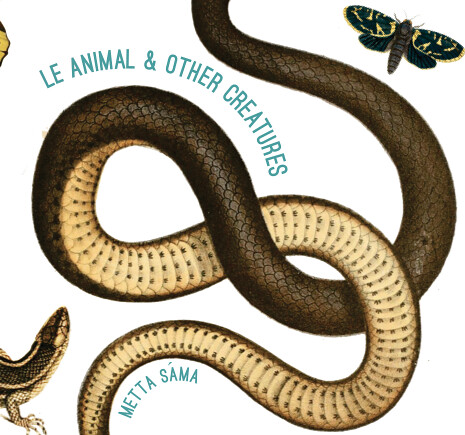

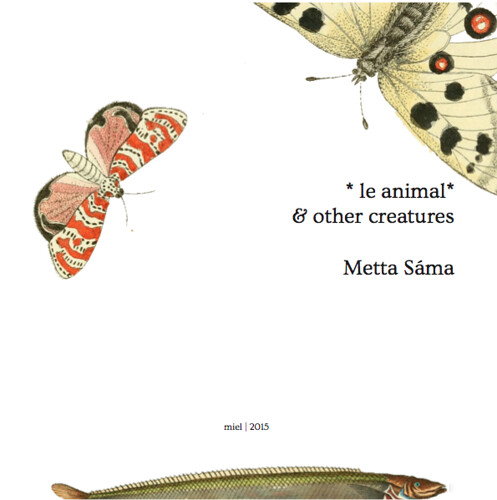

Reading * le animal * & other creatures … is visceral. Waiting for the terrors that “always find a way to enter … you turn your alarm to shiver”; we feel ‘hot slick sharp teeth breaking our flesh’; a “dry spleen” is moved; lovers hear “the grinding crunch/of pigeon bones”. Metta Sáma’s creatures are mostly unglorious: fly, spider, cockroach, human, cat, dog. Through observation, humour and the various interactions enacted in her poems she explores what is beauty and what is perceived to be ‘merely’ pigeon, and endows these unsung creatures with a magnificence of their own. We share her weeks of horror spent with the cockroach in the corner of the house, but she invites us to laugh with her at the ridiculousness of this epic battle: “You imagine a contraption akin to cat stilts and laugh until your fear hurts.” The cat she trusts is going to help her out is, finally, “belly up staring into the ceiling fan imagining you hope an end/to these terrible days.”

Reading * le animal * & other creatures … is visceral. Waiting for the terrors that “always find a way to enter … you turn your alarm to shiver”; we feel ‘hot slick sharp teeth breaking our flesh’; a “dry spleen” is moved; lovers hear “the grinding crunch/of pigeon bones”. Metta Sáma’s creatures are mostly unglorious: fly, spider, cockroach, human, cat, dog. Through observation, humour and the various interactions enacted in her poems she explores what is beauty and what is perceived to be ‘merely’ pigeon, and endows these unsung creatures with a magnificence of their own. We share her weeks of horror spent with the cockroach in the corner of the house, but she invites us to laugh with her at the ridiculousness of this epic battle: “You imagine a contraption akin to cat stilts and laugh until your fear hurts.” The cat she trusts is going to help her out is, finally, “belly up staring into the ceiling fan imagining you hope an end/to these terrible days.”

Sáma is acutely aware of the irony that “many of us whose ancestors helped build the institutions that kept us out are now financially supporting those same institutions.” But she wants “to transform these realities into art & into questions that are not heavy-handed … or rhetoric.” Despite the poet’s resentment of those who have access to ‘a safe world I can only imagine’, and despite the sound of necks and bones breaking that bubbles as a soundscape under her work, Sáma seems fundamentally optimistic. Rather than the “expectation of cardinals/fiery in the wintered sky”, she says, “Give me the rabid face/of the pigeon… always pointing toward the next hustle.”

Sáma is acutely aware of the irony that “many of us whose ancestors helped build the institutions that kept us out are now financially supporting those same institutions.” But she wants “to transform these realities into art & into questions that are not heavy-handed … or rhetoric.” Despite the poet’s resentment of those who have access to ‘a safe world I can only imagine’, and despite the sound of necks and bones breaking that bubbles as a soundscape under her work, Sáma seems fundamentally optimistic. Rather than the “expectation of cardinals/fiery in the wintered sky”, she says, “Give me the rabid face/of the pigeon… always pointing toward the next hustle.”

*le animal * & other creatures is available to pre-order now and will ship beginning August 14.

— CRJ

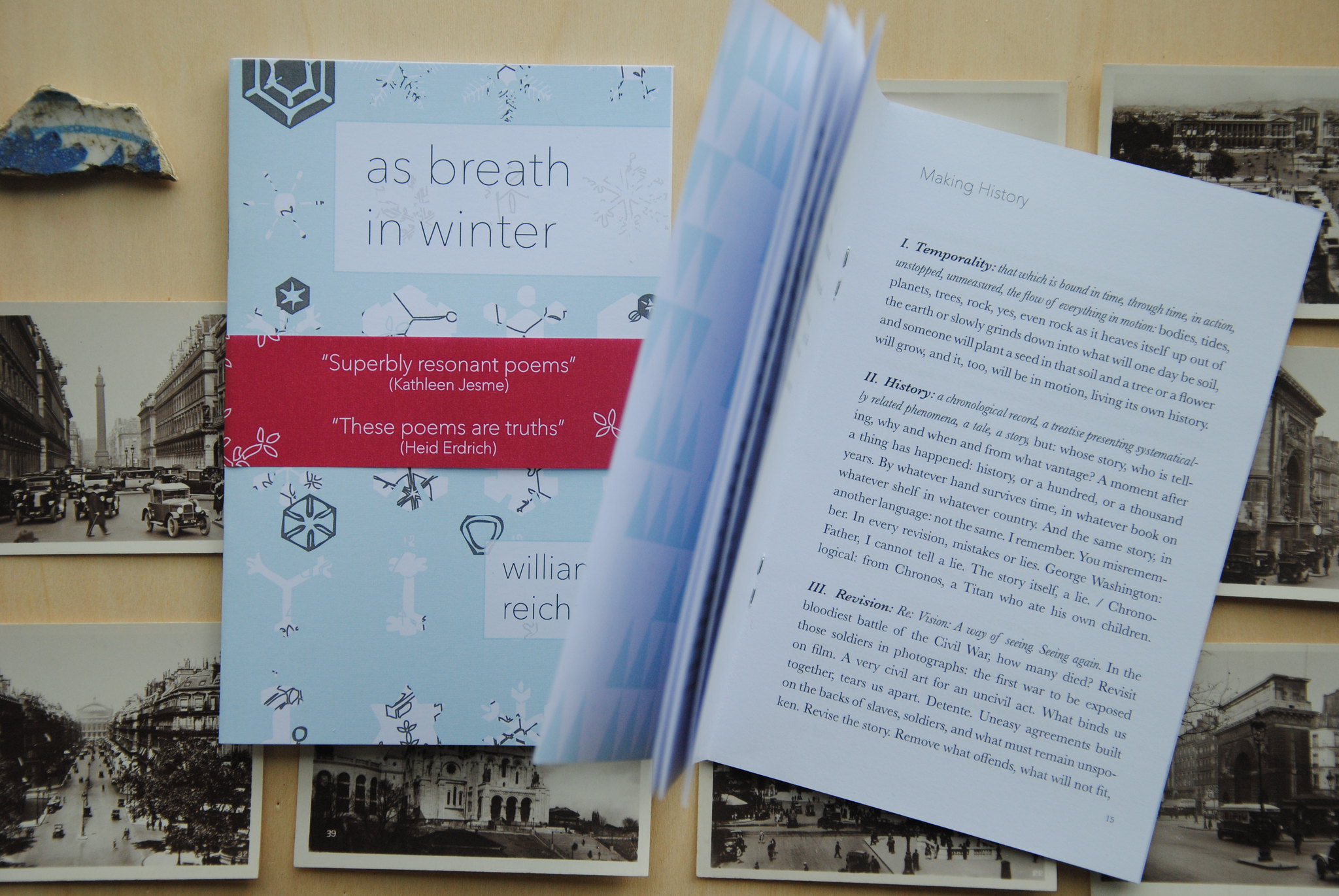

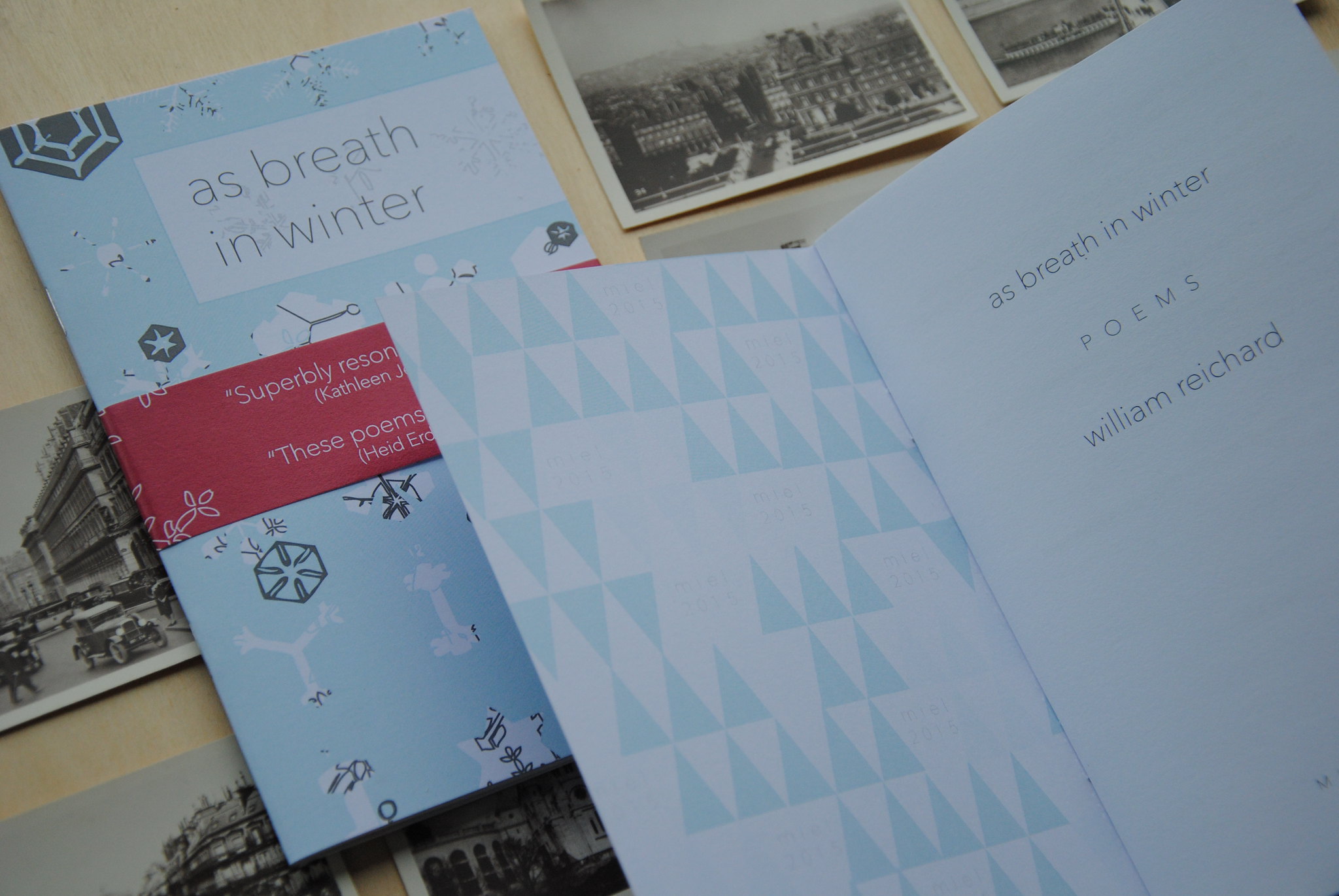

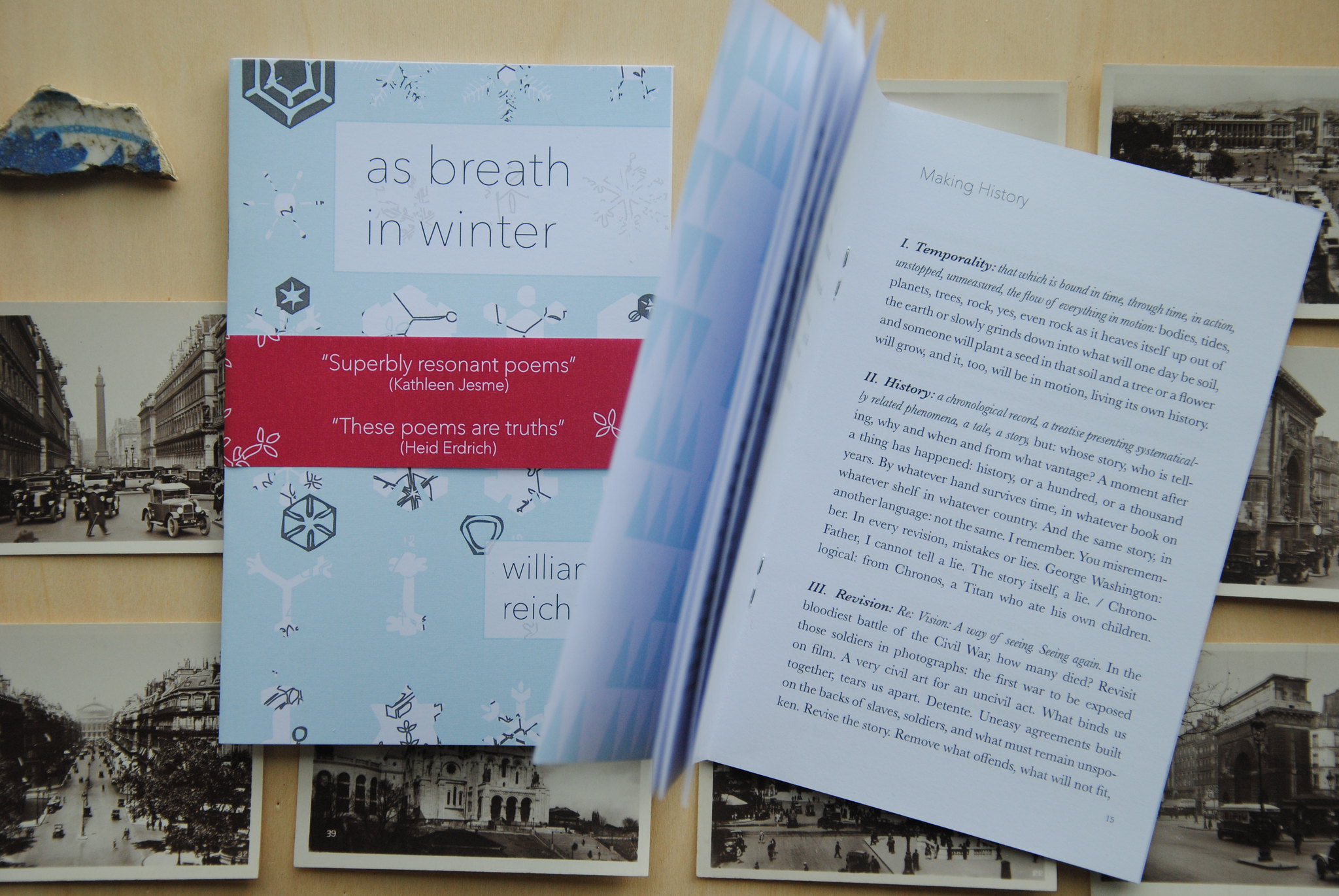

In the first of a series of interviews for MIEL, Carol Rowntree Jones spoke with William Reichard, whose chapbook as breath in winter was published this spring.

CRJ: Bill, I’d like to ask you where your understanding of poetry comes from? Do you feel as though you are part of a history of writing and, if so, how do you feel your writing takes part in that?

WR:  I believe my understanding of poetry comes from a combination of my love of language, art, and music. I love language because it’s malleable. You can stretch it, warp it, bend it, even break it. I love to look for that moment when what makes sense sits on the verge of making no sense at all. I think poetry, like any other creative art, lives on that very thin line between sense and nonsense. I often feel as if prose, fiction or nonfiction, has to operate within given parameters, though there are plenty of prose writers who push the boundaries of these parameters. Poetry, in contrast, lives without such fixed edges. Certainly, if you work in fixed forms, you’re working within very clear, established parameters. Otherwise, the field is open. We each write what makes sense to us, and the more we write, the more sense we can make of the general incomprehensibility of life.

I believe my understanding of poetry comes from a combination of my love of language, art, and music. I love language because it’s malleable. You can stretch it, warp it, bend it, even break it. I love to look for that moment when what makes sense sits on the verge of making no sense at all. I think poetry, like any other creative art, lives on that very thin line between sense and nonsense. I often feel as if prose, fiction or nonfiction, has to operate within given parameters, though there are plenty of prose writers who push the boundaries of these parameters. Poetry, in contrast, lives without such fixed edges. Certainly, if you work in fixed forms, you’re working within very clear, established parameters. Otherwise, the field is open. We each write what makes sense to us, and the more we write, the more sense we can make of the general incomprehensibility of life.

I’ve always been drawn to the visual and performing arts, and to music. I can’t really read music, but musician and composer friends tell me that my work has a sense of musicality to it, and I certainly have a lot of musically gifted people in my life. I don’t know if I’m a visual thinker because I love art, or I love art because I’m a visual thinker. In either case, visual art plays an important part in my poetry. I often write in the ekphrastic tradition, building poems around a scaffolding made from specific painting or dances or musical compositions. I look for what connects, and not for what separates, all art.

I do see myself, my work, as existing on a poetic continuum. I’ve always loved reading, and who I am as a writer now is the result of the influence of everything I’ve read up to this moment. Not all things are equal, and some forms and styles of writing have had a more profound impact on my writing than others. I find myself feeling both amused and perturbed when I encounter (usually younger) writers who say that they don’t read poetry because they don’t want someone else’s work to influence or even taint their own. Unless you’ve lived in complete isolation your whole life, have never read a word, your own work has been influenced by the work of others. I personally don’t know of any writers who are “pure” in this sense, and I’d bet I’ll never meet one. The history of literature is beautiful, and it’s a process of accrual, one layer or age building on top of the previous. In the end, you get a glorious pearl.

I guess I’d say that I’m a part of an American, free verse tradition, and this over-arching tradition is comprised of many, many singular movements. I’m gay, so I see myself as a child of Whitman, Ginsburg, and Rich, among others. I write lyric work, and I often make use of narrative, so these are also a part of me. My reading tastes are wide. I like to know what’s happening with contemporary poetry, even if I’m drawn to some styles more than others. I feel responsible, as a writer, to keep up with as much new writing as possible.

CRJ: I loved so much of your new book from MIEL. Can you tell me, in one sentence, what you would say as breath in winter is about? Tell me what interests you most about this book – or tell me other things, besides books, that might constellate around it?

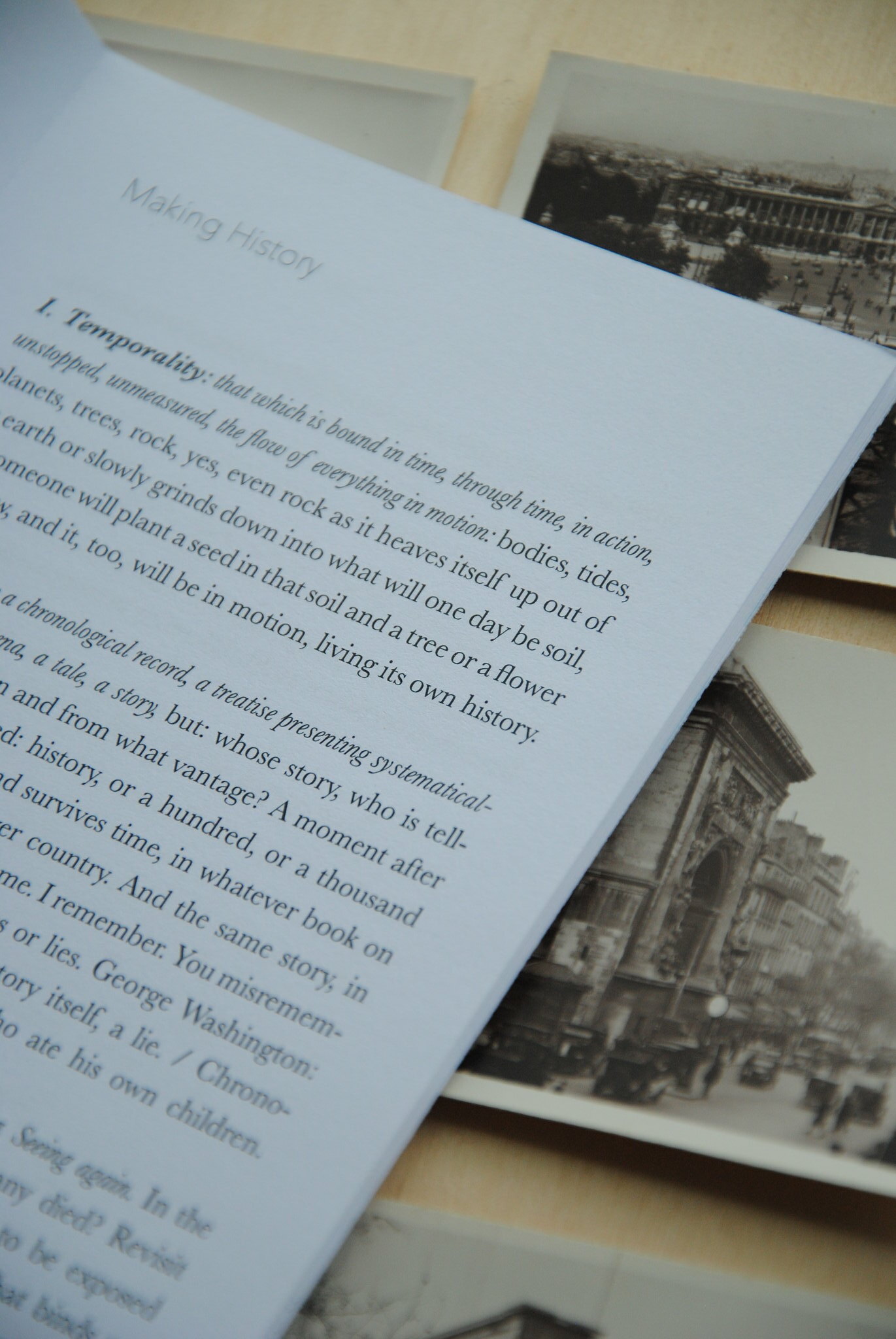

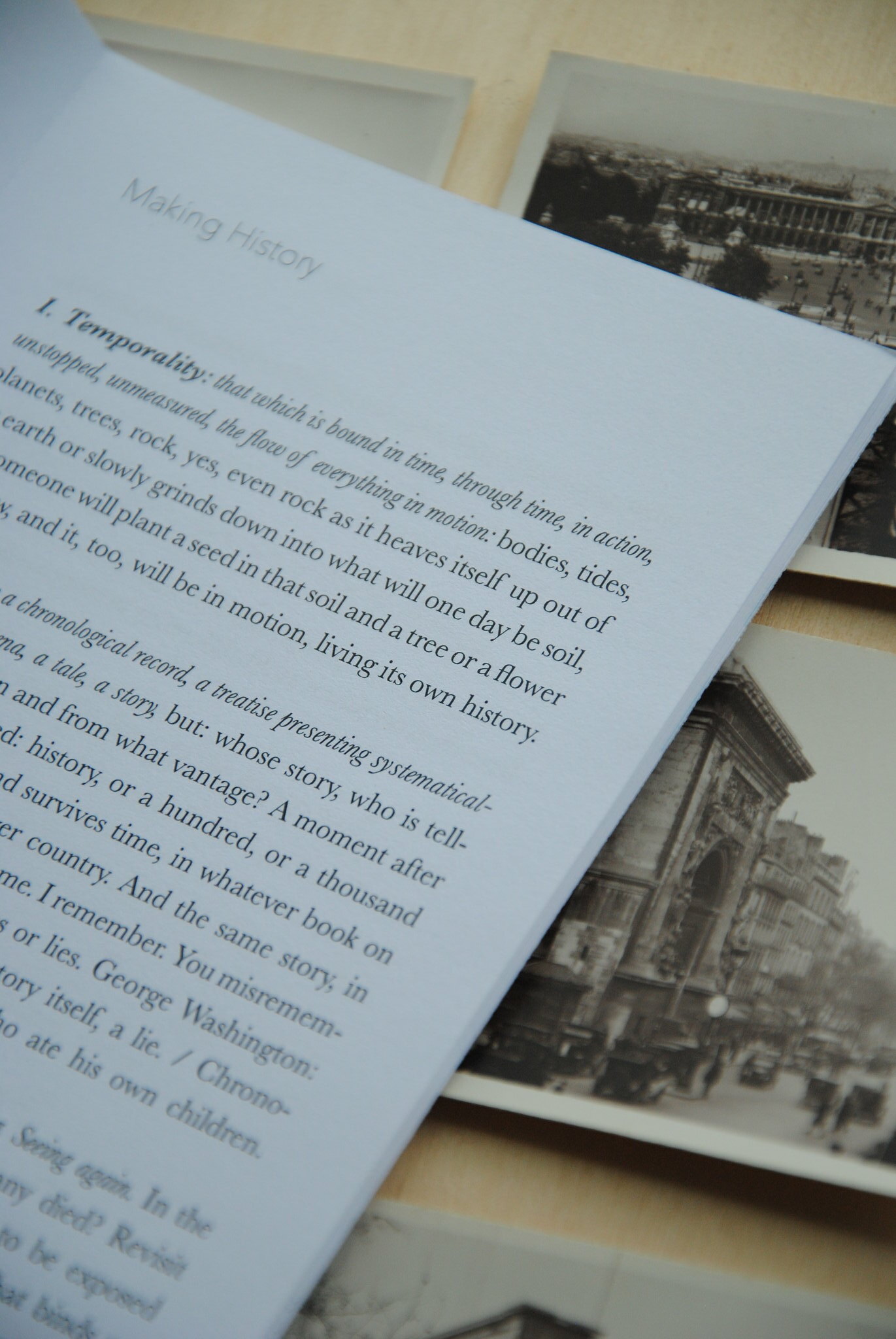

WR: as breath in winter is about ghosts, time, and an unfulfilled desire to understand the universe. I put this book together to try and make some sense out of a world that I find largely senseless. Maybe this is why any of us makes art? What interests me most about this book is the way in which it explores how our lives are linked, often precariously, to the lives of others, and also linked to the physical and spiritual world around us. We tell stories in order to understand ourselves. The stories here come only in fragments. They’re not meant to offer the reader any answers, but rather, to serve as a launch point from which the reader might enter into a state of contemplation (and that state might be peaceful, chaotic, wonderful or dreadful, etc.)

CRJ: What is your creative process like? For instance, how do you generally begin writing, and how do you go from that to the stage where you are ready to say your work ‘is done’?

WR: I like to think that I’m always writing. Even when I’m not actively putting something down on paper, I’m gathering ideas, images, impressions, and these tend to rumble around in my head for a while before they’re ready to move into print. Most of my work starts with an image that sticks in my mind. I’m a very visual thinker. As I try to capture an image, in words, I start to discover what the image is, what I want to do with it, and what it wants me to do with it. Sometimes, poems come on fast, and after a draft or two, they’re done. More often, I think for a long while about a piece, then I write it out longhand, in my notebook I keep, and then I let it sit for anywhere from a week to several months. I often go back and look at these handwritten sketches, scratch out words or phrases, replace them, realign the work, find a title, etc. When I’m ready, I type the poem in to my computer, and this serves as another step in revision. I rarely type a new piece of work directly into the computer, especially with poetry. It seems to need to be born out of my hand, in ink, first.

I don’t have one answer to the question regarding how I know when a piece of work is done. Sometimes I know immediately. I read over the poem, look at how it lives on the page, and I know that it’s complete. Usually, each poem needs to go through multiple revisions. While I revise, I’m working on two or more levels. There is the syntactical level, the specific words I select, the punctuation I use. There is the musical or sound level, what the poem sounds like when I hear myself speak it in my head, and what it sounds like when I say it out loud. There is also the visual level, the way the poem sits on the page, how it makes use of the totality of the white space available. I don’t move words around on the page just to play, though play is an important part of any creative undertaking. Page placement, like line breaks, word choice, punctuation, needs to be a conscious, thoughtful act. Some poems are never really finished. When I give a reading and perform work from earlier books, I sometimes change the older poems to suit my current standards. I don’t make a regular practice of this, but I learn something new about writing every time I write, or read, and this ongoing evolution can mean that what I thought was good enough in the past, I now find lacking, so I make adjustments.

CRJ: Finally, Bill, what has your experience been in working with MIEL?

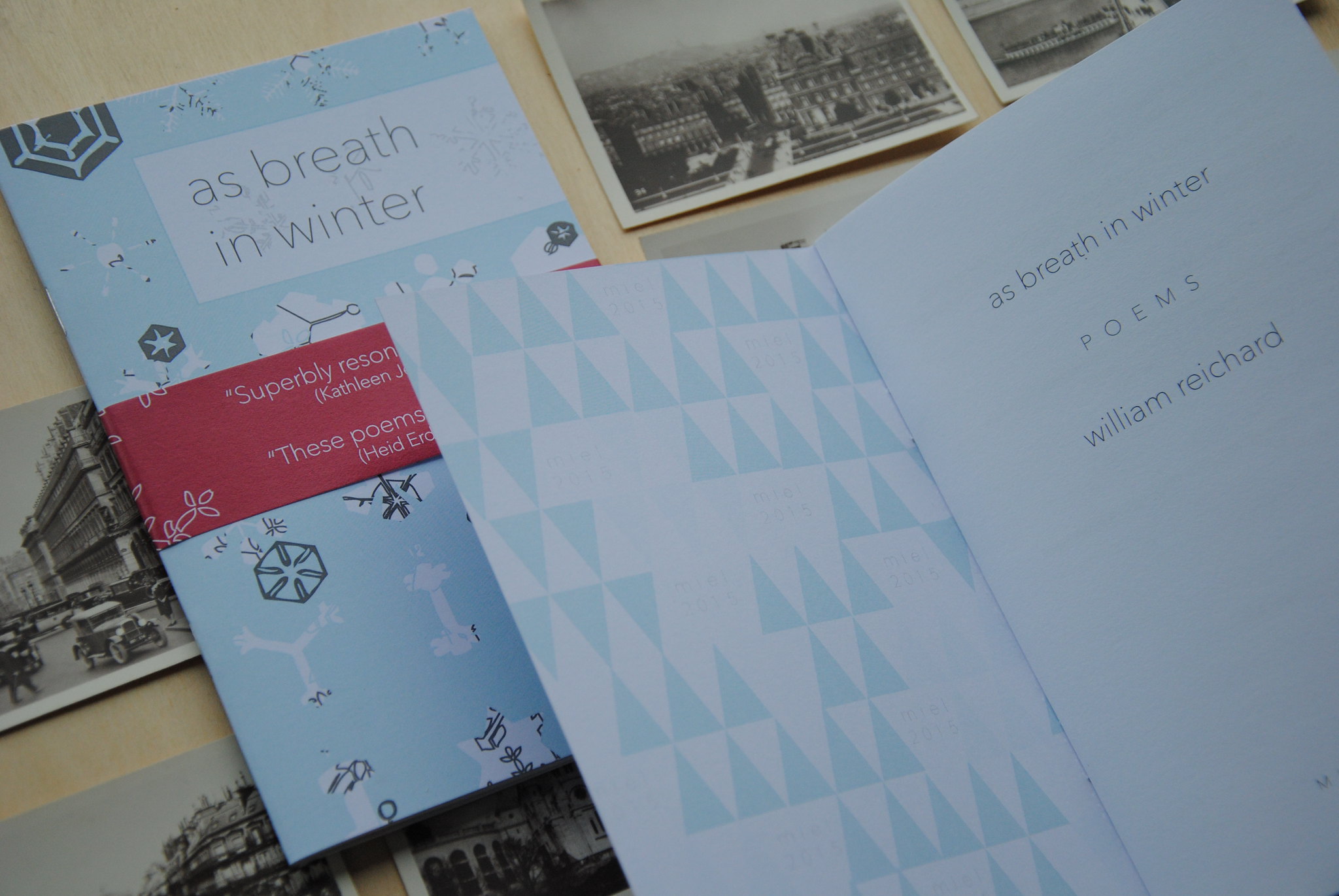

WR: Working with MIEL has been wonderful. Eireann has been gracious and patient, and the edits she suggested for my chapbook manuscript were right on target. It’s a better book because of her. Eireann first mentioned the idea of a chapbook a couple of years ago, and I was flattered that she thought enough of my work that she wanted to publish it. I love the design of all of MIEL’s books, and I’m very happy with the look and feel of mine. It’s lovely to feel that I’m a part of this artistic moment that Eireann and Jonathan have created.

Reading

Reading  Sáma is acutely aware of the irony that “many of us whose ancestors helped build the institutions that kept us out are now financially supporting those same institutions.” But she wants “to transform these realities into art & into questions that are not heavy-handed … or rhetoric.” Despite the poet’s resentment of those who have access to ‘a safe world I can only imagine’, and despite the sound of necks and bones breaking that bubbles as a soundscape under her work, Sáma seems fundamentally optimistic. Rather than the “expectation of cardinals/fiery in the wintered sky”, she says, “Give me the rabid face/of the pigeon… always pointing toward the next hustle.”

Sáma is acutely aware of the irony that “many of us whose ancestors helped build the institutions that kept us out are now financially supporting those same institutions.” But she wants “to transform these realities into art & into questions that are not heavy-handed … or rhetoric.” Despite the poet’s resentment of those who have access to ‘a safe world I can only imagine’, and despite the sound of necks and bones breaking that bubbles as a soundscape under her work, Sáma seems fundamentally optimistic. Rather than the “expectation of cardinals/fiery in the wintered sky”, she says, “Give me the rabid face/of the pigeon… always pointing toward the next hustle.”