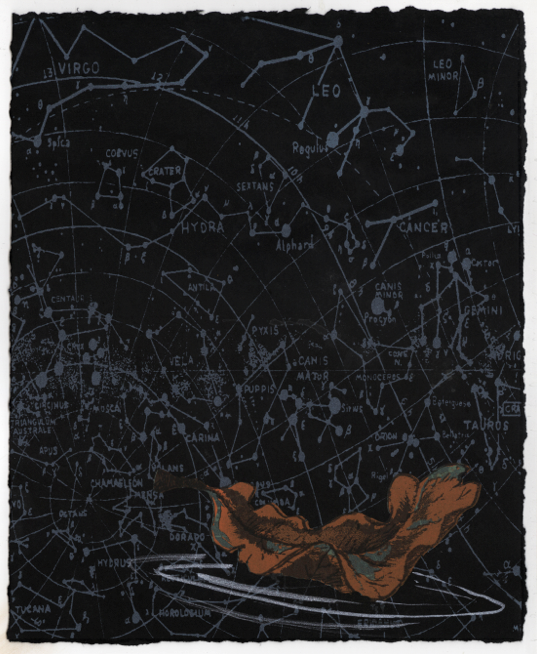

Jacob Bennett’s untitled poem (“I cannot say if the nothing I wandered was vast…”) is in 111O/7, and it was a wonderful surprise to get an email from Jacob telling us about his new chapbook, Wysihicken [sic], out from Furniture Press Books. The cover is screenprinted by Jodi Hoover, and the run is only 75 copies. (You can also subscribe to the press’s output.) It looks like a beautiful chapbook, Jacob! Congratulations. Here’s what he has to say about the chapbook:

Jacob Bennett’s untitled poem (“I cannot say if the nothing I wandered was vast…”) is in 111O/7, and it was a wonderful surprise to get an email from Jacob telling us about his new chapbook, Wysihicken [sic], out from Furniture Press Books. The cover is screenprinted by Jodi Hoover, and the run is only 75 copies. (You can also subscribe to the press’s output.) It looks like a beautiful chapbook, Jacob! Congratulations. Here’s what he has to say about the chapbook:

As far as I can tell, one of the most common questions posed to poets about their work, by poets and non-poets alike, is this: “What is it about?” When people ask what my chapbook Wysihicken [sic] (Furniture Press 2014) is about, I tell them that it’s not “about” the Wissahickon Creek, but that the creek and its surroundings are central to the human and natural history that are the book’s true subjects. I would never have begun writing the poem if I hadn’t seen and smelled and felt the physical space, been inspired, I suppose, by the same natural beauty that Poe admires, noting the “high hills, clothed with noble shrubbery near the water, and crowned at a greater elevation, with some of the most magnificent forest trees of America.” And I never would have continued to shape the poem, transforming it from a descriptive idyll into something more critical, had I not stopped to read the various placards lining Forbidden Drive, a gravel road running along the stretch of the creek that falls within the Philadelphia city limits. One placard describes modern attempts at preservation efforts, another the history of milling along the steep banks, while another connects the dots between industry and public health by explaining why what was once a public drinking fountain, with its extant inscription “PRO BONO PUBLICO ESTO PERPETUA,” is now a bricked-in edifice. And there’s the “Indian” statue that is supposed to stand in memoriam for the decimated Lenape people, but which, revealing the half-earnest sentiment behind the monument, depicts a chief wearing a war bonnet worn by tribes in the Western Plains, far from the banks of the Wissahickon. So, while the creek and the park around it are important as preservation measures, and serve to provide recreation for walkers, runners, hikers, bikers, equestrians, and anglers, the land and its history are tainted by colonial hypocrisy, racial domination, and industrial bottom-lining, and so also serves as a microcosm of American history. And I wanted to capture the mix of awe and anger I felt in response to everything I learned, and hope the poem does some justice to what my emotional and rational minds were processing.