Fellowships: For the 2016 season, Dickinson House will award two fellowships to writers and one to a visual artist. One writing fellowship is reserved for a writer living in a location with a population of fewer than 400,000 people. Fellowships cover the full rate for a two-week residency. 2016 applications open November 1st, 2015 and close December 15th, 2015. Decisions will be made by jury (reading blind) and announced in February 2016. Writers of color, women writers, and LGBTQ writers are especially encouraged to apply. (Please note: travel stipends are not included at this time.)

Application basics for Writers:

- A brief essay (up to 700 words) answering the following questions: How do you conceive of community? Why are you applying to come to Dickinson House at this point in your work? What can we offer you—and what will you bring?

- Your plans for your residency

- Any dates you are not available to be in residence

- Ten pages of recent work (prose double-spaced and paginated)

- If applicable, brief statement of financial need/circumstances

- Details (email and relationship to you) of two references who can speak to your way of being in community

- Application fee: $18

Submit November 1 – December 15: via Submittable

Application basics for Artists:

Interested in supporting Dickinson House and the other writers who stay here? Our Writers’ & Artists’ Residencies make our fellowships possible. Applications are accepted on a rolling basis for fee-paying residencies. Rates start at €700/week (approximately £515/$790) and include full board. More information is here.

A “woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write”. Woolf finishes that statement with ‘fiction’, but I think it is true for all kinds of writing. And also I think ‘woman’ does not have to be ‘woman’. I think many of us need spaces of our own in order and in which to write. Sometime these are called ‘safe spaces’, an appellation met with derision (as if it is somehow an outlier to want to be safe, where ‘safe’ means ‘able to critique dominant structures without fear for one’s job/work/life/dignity/…). But really these spaces, which have always been accessible to those with power (historically speaking from a Western point of view, to wealthy, white, Christian men), are just places we know we can go into for the extended, vulnerable undertaking which is making new worlds and unmaking or remaking the ones we have.

Not long ago, the editor of a well-respected magazine made it clear that he is unwilling to examine his aesthetics and vision for unconscious bias, and, therefore, that making openings in his magazine for writers whose work might fall outside that aesthetics is not a priority. Where am I going with this. As a white person, I was not taught to think about race in literature, except when reading a black writer, an Asian writer…because ‘white’ was unspoken. White meant ‘normal’ and just literature. White was background. Ordinary. The norm from which difference was established. Which meant also that people who wrote like that (meaning: descended from a long tradition of writing mostly by white men from Europe; later also by white men, and some women, from Europe and the US) just wrote, and everything else was inflected, tinged by the invisible but sensate presence of blackness, brownness, other-bodiedness, other-genderedness (the prefix ‘other’ already separating from a presupposed norm), class (meaning the fact of labor or the question of means, i.e. the vulgarity of talking money)…. As though identity, or the politics thereof, were a kind of contaminant. As if the invisibility of whiteness were not a politics of its own. As if a literature that invisibly aligns itself with whiteness (by saying ‘canon’ or appealing to certain habitual ways of making text) were not a politics. As if neither required examination. As if preferences were natural and not conditioned. As if I could ever just read a text by a writer not operating in that white sphere, without the history and practices I had been taught, surrounding literature, acting as lenses (lenses that generally say, this is no good, which means this doesn’t look like what I’m used to, without the hmm, why am I used to what I’m used to moment).

In response to this, someone in a conversation floated the idea of editors of journals who are committed to supporting the work of writers of color (and other minority writers) might have a sort of badge on their site. Some discussion followed, pointing out the difficult logistics of this (would it be quantified? Who would adjudicate? How would decisions be enforced?) as well as the way in which a ‘badge’ might operate essentially as a congratulations or reward for (white) editors who are doing what they should do anyway, i.e. reading openly and widely, soliciting from writers of color, examining their own learned and invisible biases (and the relation of these to power/white supremacy/kyriarchy…).

Let me interrupt myself to say I know a blog post is a short forum for a long idea. This is more complex than I can do justice here. And pausing for a moment on this idea should not erase the fact that this momentary thought is a small one in a long chain of moments which are experienced and narrated in complex and multiple ways by the people who live in and through them, and that I am late to this conversation. I mean that I am by no means positioning myself as a be-all, end-all. And this text-moment is not thorough or complete. And my own education is ongoing and humbling, and much of it has been provided to me by the writers of color, many of them women, who tweet, write blog posts, and otherwise make their thinking publicly available.

But: I would not have a badge like that on 111O. I do not want to be noticed for publishing women, writers of color, or any other ‘underrepresented voices’, even though that is absolutely what I feel my remit is. I do not want to call attention to that. That seems self-aggrandizing and goes against my gut sense of what my job is. It is my responsibility as an editor to seek out those voices and to listen to them and also to make space for them. That is basic. That is not something to ask for acknowledgment for. That is supposed to be the fundamental work I do as an editor: look for writing that revises the world, help it be itself fully, make space for it.

If I am serious about the work of dismantling white supremacy, that means—for me—prioritizing a change in the way I read and how I think about what literature is, how meaning works, and how the invisible paradigms I’ve been taught to take as given constrain my ability to see, feel, and listen. I don’t want a badge to tell anyone how I’m doing. I don’t want an official seal that somehow says “accomplishment unlocked!”. Paying attention to privilege is ongoing work for me. It doesn’t have an end moment. Learning to read again is perpetual and necessary; I have thirty-plus years of having been taught/having learned to read in an erasing way. If writers of color, queer writers, trans/nonbinary writers, women writers are going to feel comfortable with my publishing them, I think it will only happen if/when they can see that I have an ongoing, extensive commitment to hearing them and to supporting work regardless of whether I have learned to read it yet.

I deeply desire for MIEL and 111O to be homes—rooms—for writers who need that space, writers who haven’t necessarily had that space, and writers who don’t feel welcome in other spaces by virtue of the way who they are intersects with how they write. I want to make a space that reads new writing with rigor, attention, and love. That’s what I feel called to do. I don’t want to talk a lot about it because I also feel that my job is to be modest, humble, and invisible wherever I can. But I wanted to state my beliefs here, too, so that if anyone is searching they can see where MIEL stands.

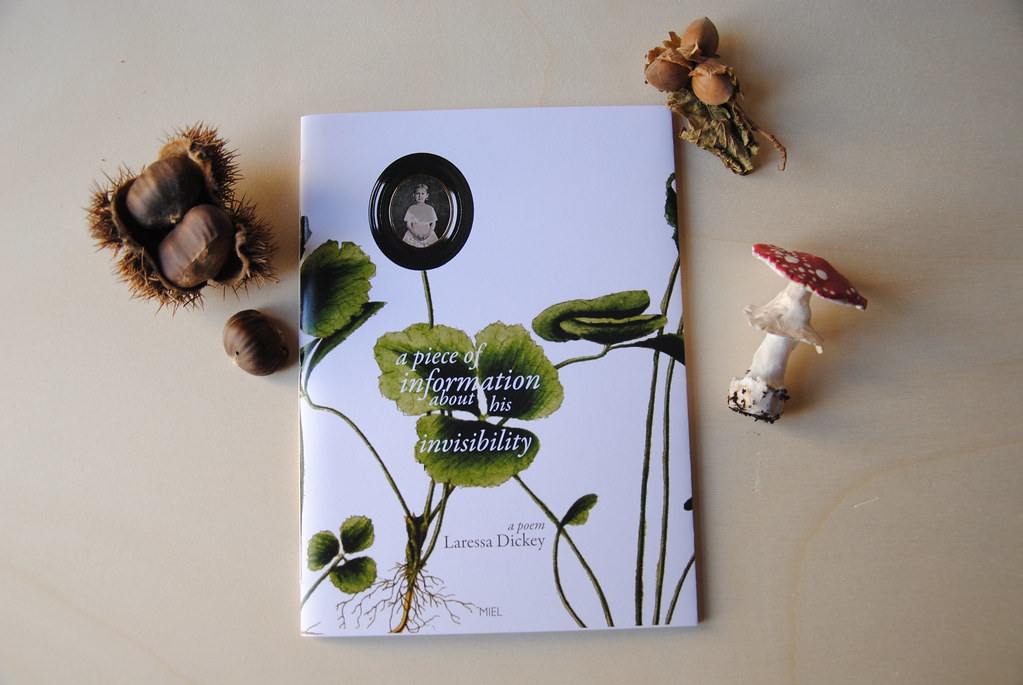

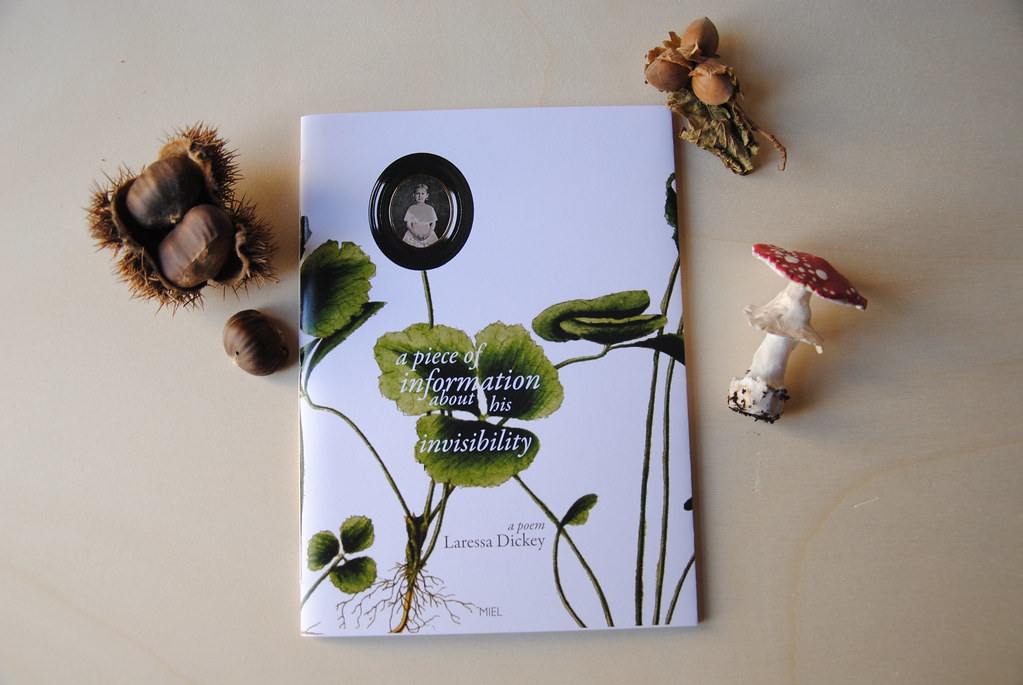

When I told Laressa Dickey that I, too, was tired of her work being passed over in contests and open reading periods, and that I thought it was worth publishing, and hey, what if I published it (in December 2011), I knew almost nothing about publishing. I knew almost nothing about book design. I set off, as with most things I do, backwards: first committing to making the books, and then figuring out what I needed to do to become a press.

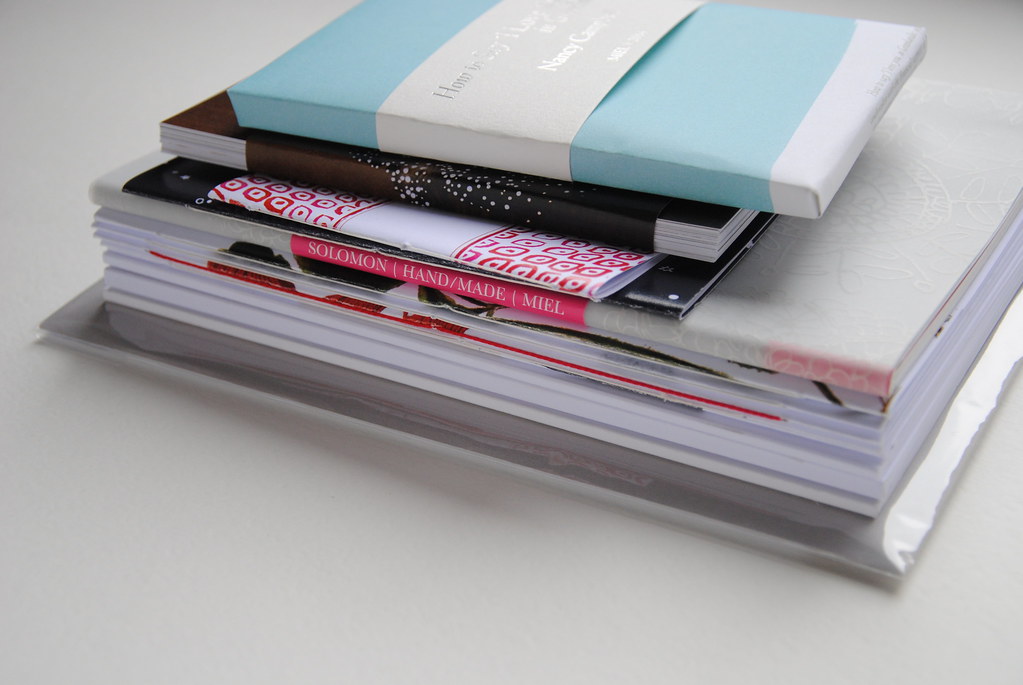

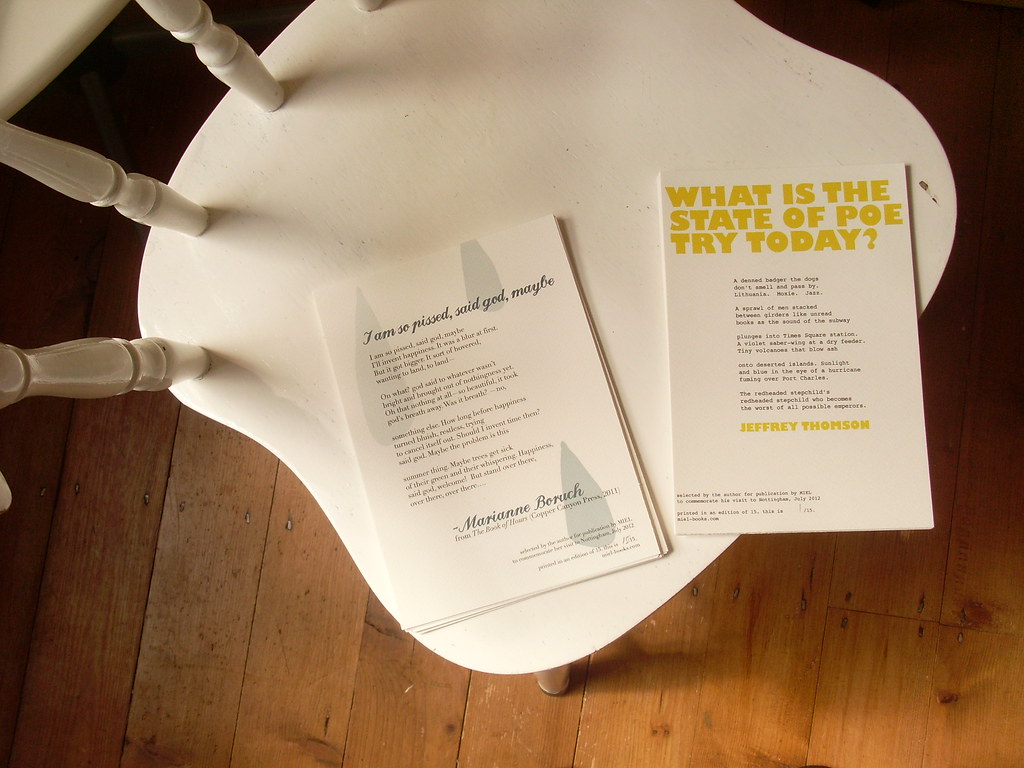

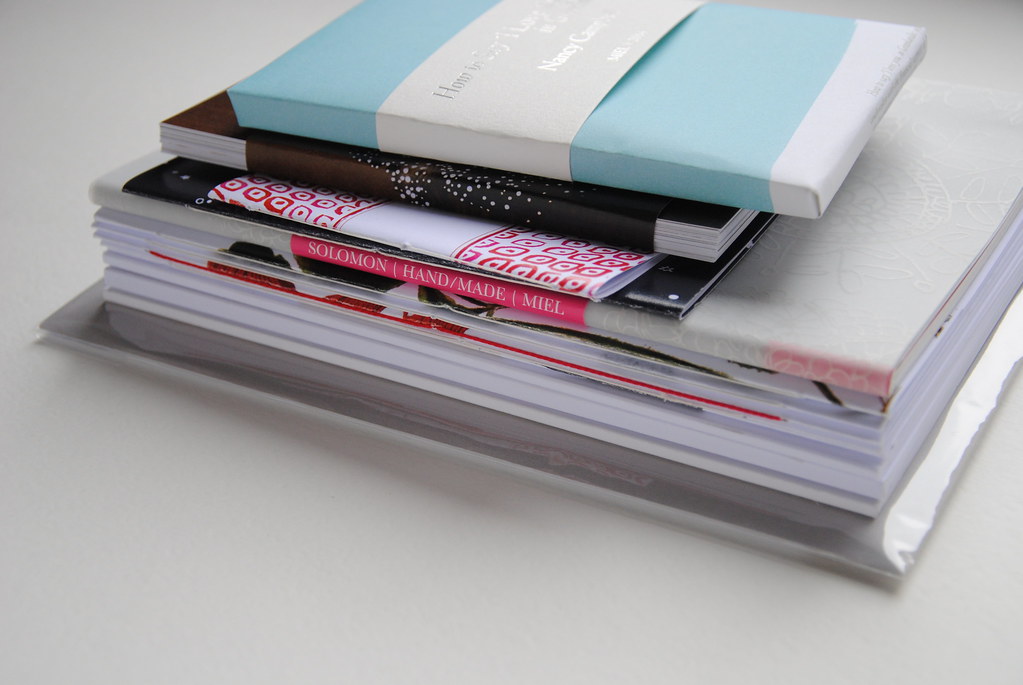

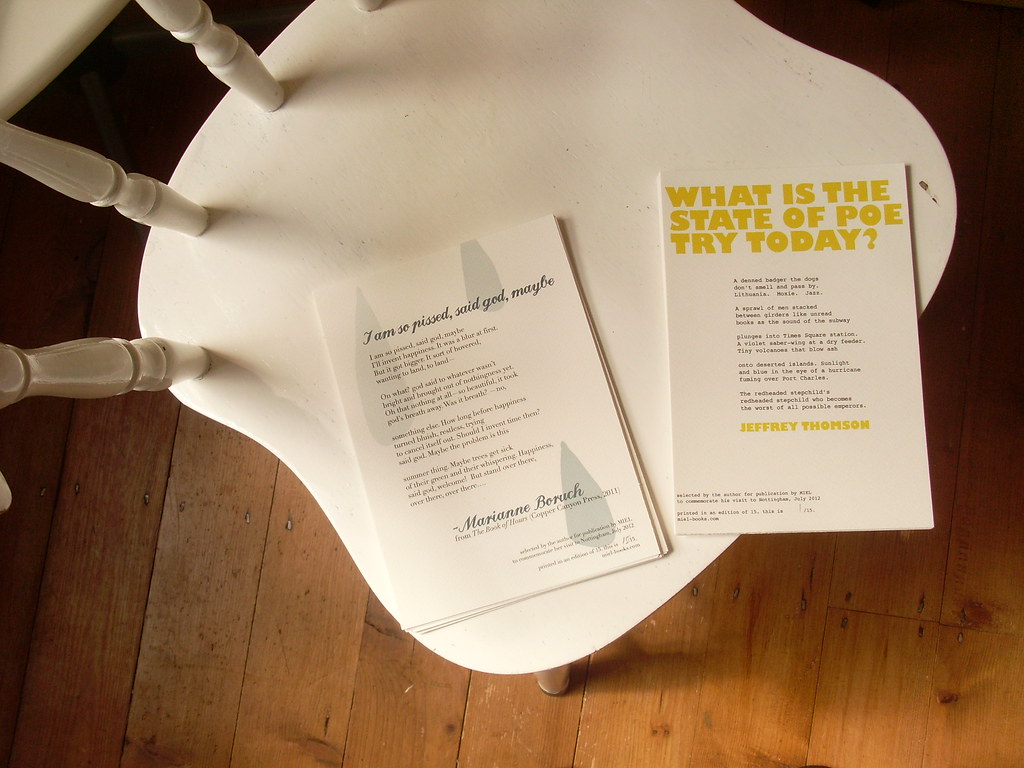

When I think back on the four months between telling Laressa I’d make the press that would publish her work—why not; lots of writers have done this, I said—and launching the first two of her chapbooks alongside Neele Dellschaft’s first chapbook, I remember scrambling to get ISBNs and a business address. I remember watching lots of videos on YouTube in order to figure out how InDesign worked. I remember getting the first batch of covers and it being a real lesson in measure thirty-six times, send the files to the printer once. Oops. I remember folding and binding on the red table in our workroom with Jonathan and Neele. I remember getting those tiny broadsides in the mail from Andrew Schroeder (for Josh Wallaert’s chapbook and Laressa’s third and fourth chapbooks).

As with lots of things I do, and for better or for worse, MIEL began as a piece of play. A game. Let’s imagine what could be, and then let’s do it. That’s a manifestation of my impatience but also of my belief that things are possible and that individual people can make objects and spaces (that we don’t have to wait for the ‘professionals’ to do it, and that we don’t have to make things that act, look, or feel the way ‘real things’ do—we can make our own, in our own way, with the terroir of our individual capabilities and experiences). The incredible thing I learned is that once you start the game, people believe it’s real. And they say yes to things like you publishing their books, even in different formats (like the postcard edition of Nancy Campbell’s How To Say I Love You in Greenlandic, which sold out within a year of publication). And then reviewers say yes to reviewing them. And people, incredibly, show up to buy them.

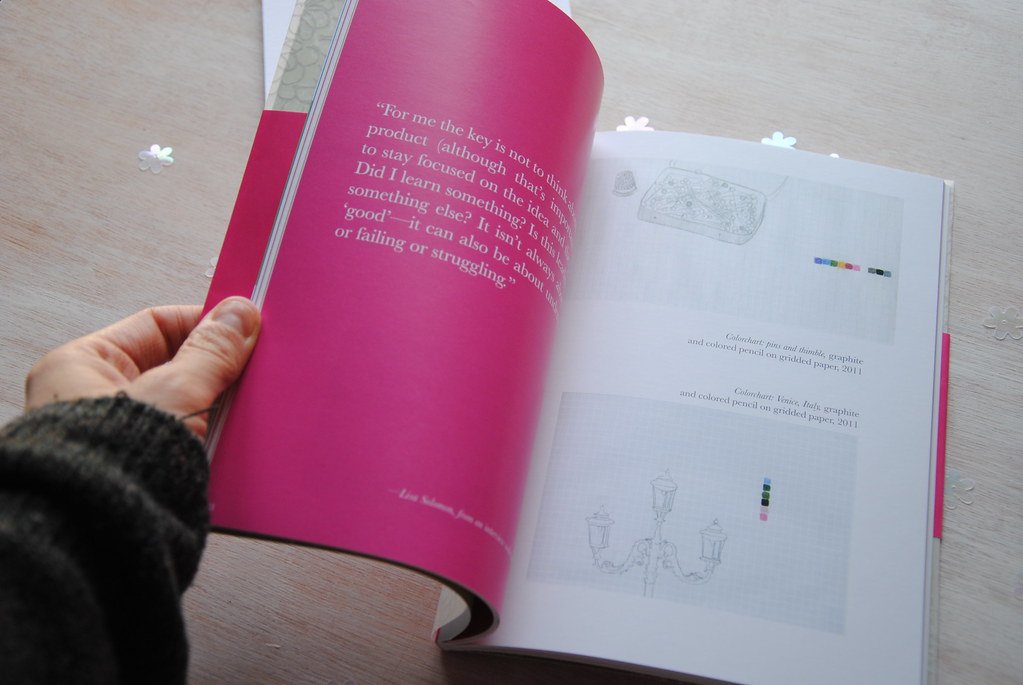

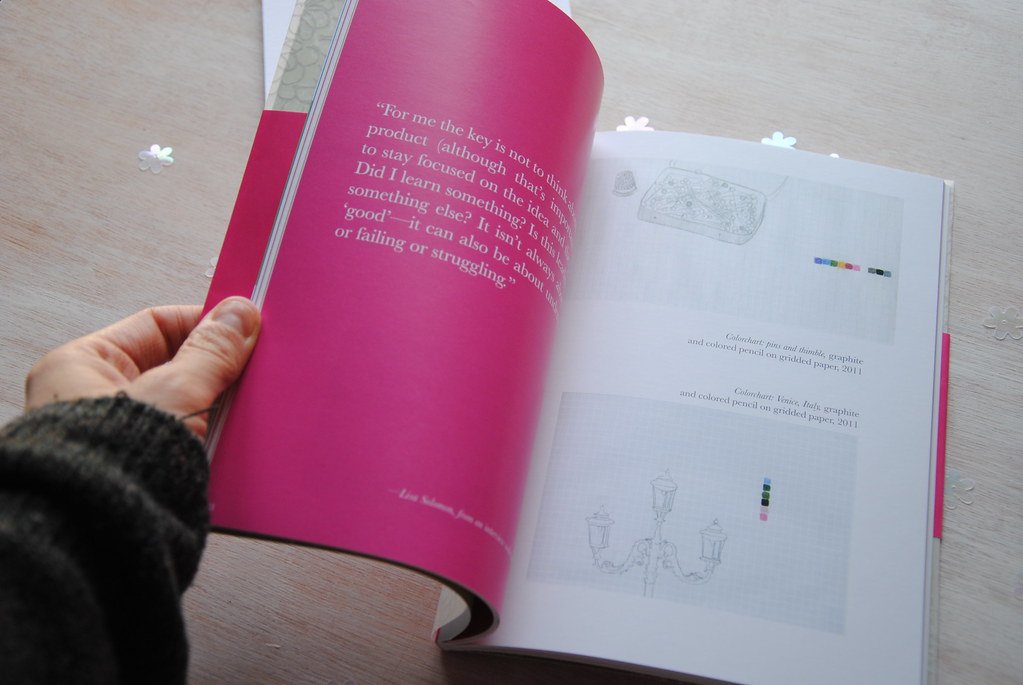

Designing and publishing Lisa Solomon’s book was in many ways a turning point for MIEL. Prior to this I had used my own savings to pay for book printing (our books generally cost between €200 and €400 to print; at that time I had some work and cheap rent, and I used what was left over to print books). But Lisa’s book is full-color and bound in signatures. It was going to be impossible to publish without assistance. I applied for an Arts Council England grant (thanks, ACE!), which paid for the printing and my time designing the book. Working with Lisa on this was such a gift—her trust in my work really made me aware of the relationship between me as a book designer and editor and the writers and artists whose work I want to support. The money from the Arts Council, and Lisa’s trust—and the book itself, which is the most ‘real’ book we’ve published in design terms (it has a spine, I mean)—made me realize that MIEL could be play, but it was also and simultaneously serious.

One constant in the press work has been the pleasure I take in all aspects of book shows and small press fairs. Everything from designing and building displays, to interacting with visitors: although it can be draining (long days, lots of people, sometimes I forget to eat enough), it is so great to get to talk to people in real time about these books, and to watch them enjoy them, pick them up, read them. As a micropress, lots of book work—like lots of writing—is isolated, quiet, uncompensated. Being in rooms with people, seeing and participating in the life of small presses and of books, is an unmitigated joy.

When I think back now, I’m amazed at how much has happened in the past three years. (MIEL launched its first three titles on March 16, 2012). There are books now that didn’t exist then. I know how to do things (use InDesign and other parts of Adobe CS, market books, manage inventory, offer editorial guidance, work with printers) that I didn’t before. I’ve gotten to meet and correspond with so many great writers and artists, have hosted readings, have helped make connections between writers and other presses when the work wasn’t a fit for MIEL. Not trying to toot my own horn. Just kind of incredible to me how at one point there wasn’t and now, despite the ways in which I still struggle (managing the workload without getting overwhelmed) or worry (the panic of oh my god did I send the proofed version of the manuscript to the printers?!), there is. And the is includes books like Kristen Case’s Temple and Shana Youngdahl’s winter/windows and Megan Garr’s Terrane and Bethany Carlson’s Diadem Me and Jonterri Gadson’s Interruptions and Rachel Moritz’s how absence. And more are coming. (!!!! Although I tend to get bogged down in worry—will the books do justice to the texts? Will they please the writers? Where will the money come from, oh god, the money?—when I step back from my worry I realize how thrilling, really, in a physical way thrilling, it is to be able to make these books.)

So thanks, writers and artists, for trusting me to put your writing and art into the world. And thanks, customers, for buying the books and other things, and allowing me to continue. Thanks also to my parents, who, despite my protestations, order every book (don’t do that! I will send you copies for free!). Thanks to the Arts Council, and to Writing East Midlands, and to the Small Publishers’ Fair and to Free Verse and to States of Independence, who made it possible for the books to exist and provided venues where people could encounter them in real time. Thanks to the reviewers who’ve taken time to read and think about the writing. Thanks to the people who sent work to read during the open reading periods each year. Thanks to Richard of Tompkin Press in Nottingham and Tom Jessen of Foxglove Press in Maine for working with me, producing the books, and tolerating my beginner’s mistakes. And special thanks to my friends, especially Jon, Neele, Matt W., Carol, and Laressa, who have supported me and believed in the press all along. Thanks to Jonathan who as usual made things possible (and always talks me down when I think I’m being silly to try things like this). Three years! Let’s have a few more.